Litter Winter/Spring 2026

antidotes to toxicity

a letter from the editor

Welcome to the Winter/Spring 2026 issue of Litter, the journal of the Ecological Design Collective. This publication emerges from a shared recognition that toxicity has become a defining condition of our time, manifesting through chemical pollution and environmental degradation, as well as social inequities, extractive economies, institutional violence, and systems that erode collective care. In such a moment, the work of ecological design must move beyond diagnosing harm and toward cultivating the practices, relationships, and imaginaries capable of countering it.

This issue of Litter seeks to make space for those antidotes. The contributions gathered here explore how communities, designers, artists, scholars, and writers are responding to toxic conditions with care-centered strategies, regenerative imaginaries, and collective action. In centering antidotes to toxicity, Litter Winter/Spring 2026 affirms the power of collective visioning, imaginative responses, and design with the more-than-human world to confront harm and build conditions for life to thrive. We are grateful to all those who contributed and thrilled to share this issue with you.

— Jessie Croteau, Editor

how we might identify, imagine, and design responses to both literal and figurative toxicities—from polluted environments and harmful systems, to social, political, and psychological poisonings?

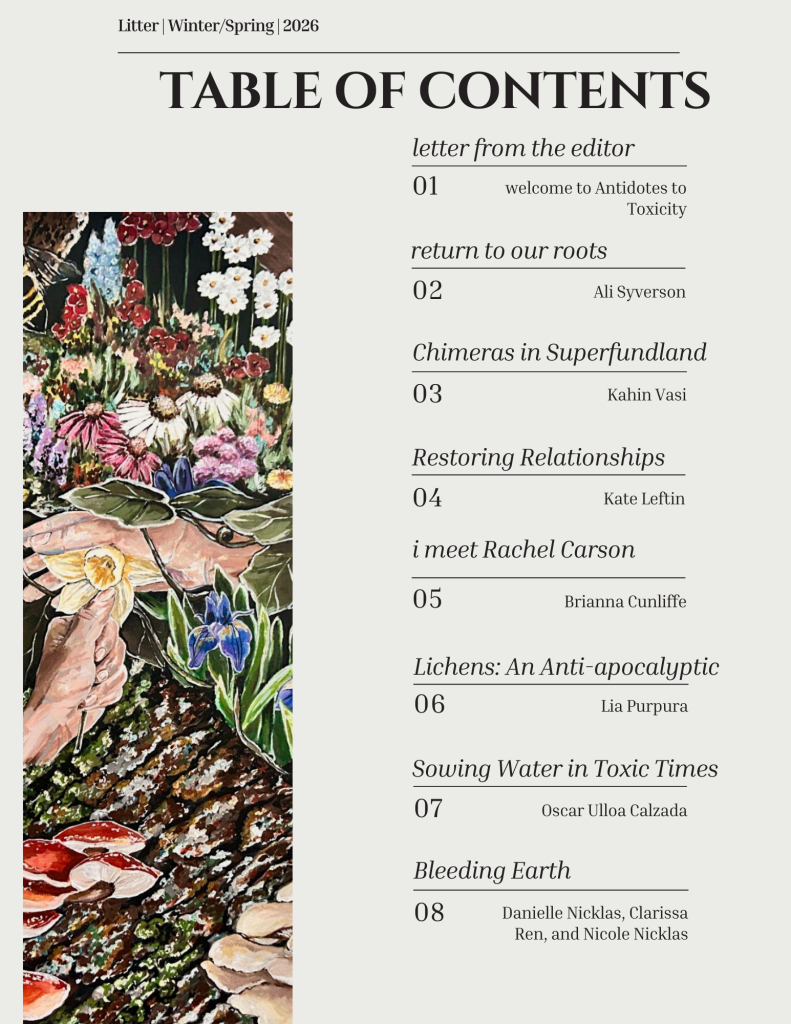

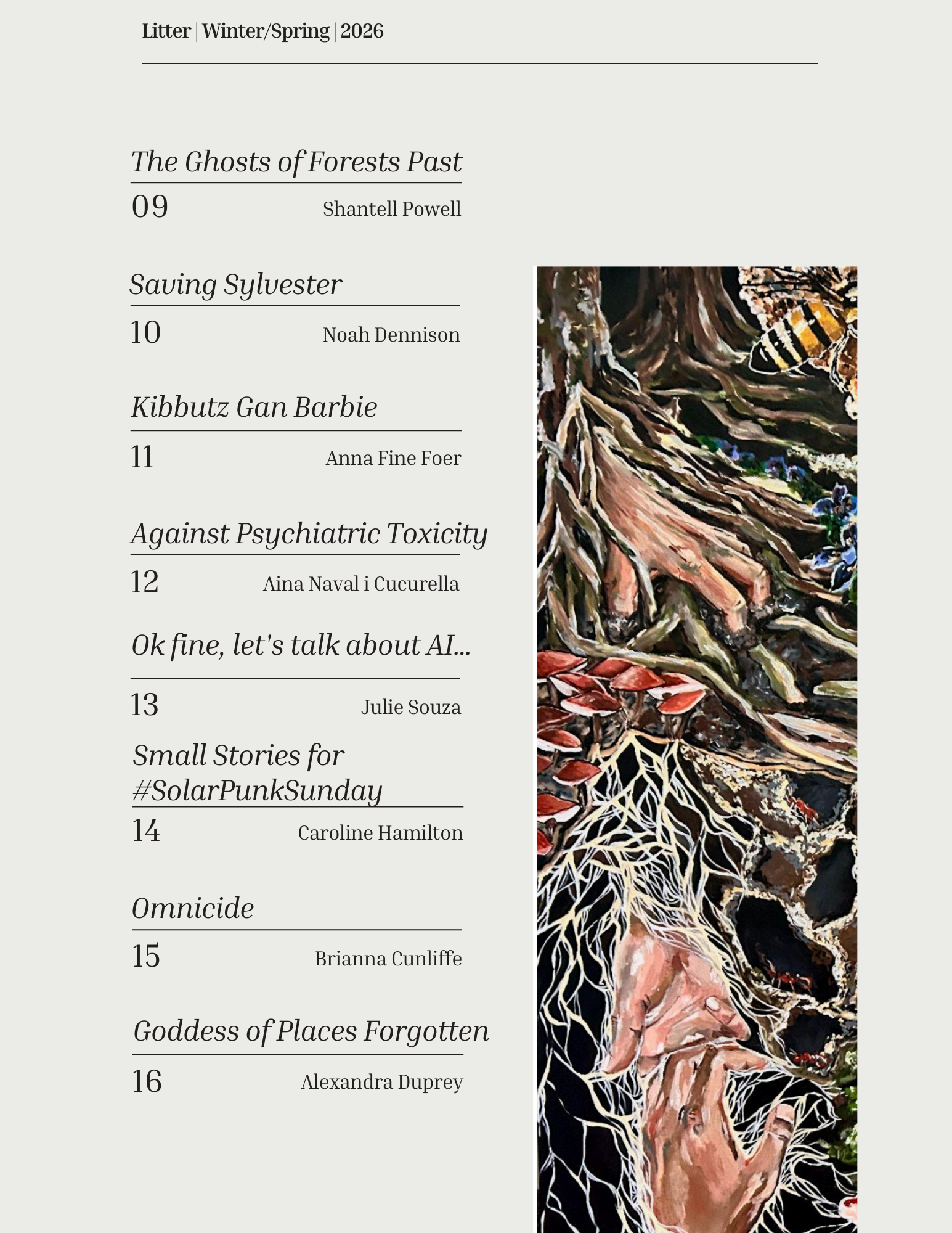

Return to Our Roots

Ali Syverson

Painting, 36x48in acrylic on canvas

Return to Our Roots is a visual depiction of the ways that natural ecosystems show us how we can support, celebrate, and lift up one

another for the sake of a stronger community and system of aid and

mutualism. From ant colonies working together, mycelium connecting

and supporting entire ecosystems, and interplanting of beans, squash,

and corn to show strength in diversity — Return to Our Roots shows that we have much to learn from our natural environment. The hands

intertwined into the roots, flowers, and trees symbolize what we are

made of, and that to which we will eventually return.

Chimeras in Superfundland

Kahin Vasi presents a speculative design project that reframes toxic Superfund sites as active landscapes of repair, proposing the deliberate exposure of buried industrial detritus to foster new chimeric ecologies, symbiotic lifeforms, and long-term processes of planetary healing beyond human timescales.

Kate Leftin

Restoring Relationships as an Antidote to Toxicity

It has become common to call our current times the age of the “polycrisis” or even “the meta crisis”. Rampant climate change and ecological collapse threaten to unravel the natural world and our civilization that grew up in it. Meanwhile, political polarization, political violence and increasing inequality threaten to unravel the social fabric that weaves our lives together with insidious threads of toxicity.

The root of this toxicity is separation that runs deep, like a spreading cancer that can no longer be ignored. We feel separated from each other, from nature, even from ourselves. We feel it every time we avoid the neighbor that has opposite political opinions, every time we shut down as the headlines show another natural disaster, every time we pretend everything is fine when it’s not. In this place of disconnection, we have let distrust fester, and we retreat further into our silos. In the spaces between us, living out our separate lives in isolation, the toxicity grows. We try to find our people, but while we do, we become more alienated from the people that don’t agree with us. It makes our communities brittle amidst a myriad of crises and perpetuates them.

i meet Rachel Carson in my dream, at the edge of the tide

close your fist around broken glass in

a gesture of remembrance for the sea

we walk together, amongst

insoluble yesterdays, and the beating

stored wrath of every unresolved decibel

turns to shrieking sound, and the rockweed shivers and endures

and when the water is wrung out

with its tears and recedes, it

unfolds, reconciles.

and we emerge to see what new world has now been made

this attention which is our womens’ prayer

a few days off-kilter from the lunations

it comes into its strength:

tides, neap and spring. carving new maps, snakeskin,

to rue and to shed

these currents have delivered me, gasping, onto each refracted image

of these, our meeting-places. cliffs, coral, ceaseless sands, they have rendered me one

among the nascent

creatures seeking shelter in its cradle, finding, sometimes, shelter, but sometimes the

battering spring

sometimes the dredged-raw wound and the gasping minnow

sometimes the ancient snared in plastic, sometimes collapsing stilts where

flag-swaddled babies play in the even-now ghost of a home

resilient or parasite? do we endure or haunt? do the mollusks?

we kneel and watch the anemone, crooked and heedless, dance in the silt

open your hand, she tells me, and amidst the drying blood

from the shards of it all, a smooth, round stone

translucent and warm. a merciless healing

taking place

even now

By Brianna Cunliffe

Lia Purpura

Lichens: An Anti-apocalyptic

Lichens were never the subjects of still lifes. They might have been if we didn’t love such lavish measures of the end, our earthly desires and vanities arranged by the Dutch masters as fat wheels of cheese, candles pooling creamy wax, bright lemons peeled to their velvety pith, pheasants curing on filigreed trays, and over it all like a pearly, held breath, late sunlight through a kitchen window briefly warming eggs in a bowl, icing the stems of chalices, everything paused, posed, and gloriously sheened before the coming dark.

Oscar Ulloa Calzada

Sowing Water in Toxic Times

Toxicity in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, Mexico, names a condition where ecological decay and political design converge. This slow violence, born from decades of extractivist expansion and administrative centralization, was inaugurated by a 1967 presidential decree proscribing groundwater extraction by Ben’zaa communities. This juridico-technocratic device reconfigured water from an organizing landscape presence into an object of calculation, converting a hydrological commons animated by ritual into an agricultural expanse for production. In doing so, it subordinated ritual and communal assemblies to managerial abstraction and imposed a monistic rationality upon a plural world.

This register of toxicity is thus more than chemical; it is at once bureaucratic and ontological. It manifests as a slow poisoning of the trust between communities and aquifers, the depletion of collective assemblies, and the silencing of more-than-human entities—such as rain deities and mountain guardians—whose reality persists in situated ecologies of practice (Ulloa 2024). By circulating through institutions and imaginaries, this toxic order recalibrated reality itself, narrowing ontological possibility to a single, normative regime.

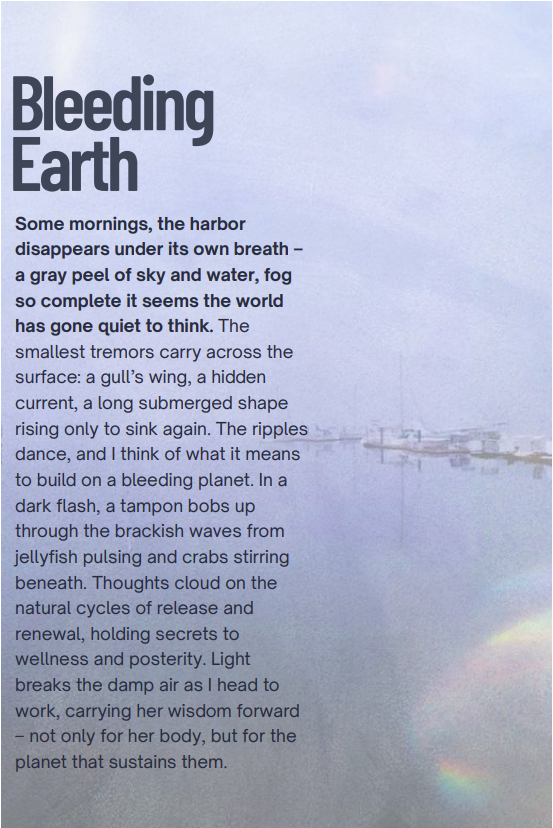

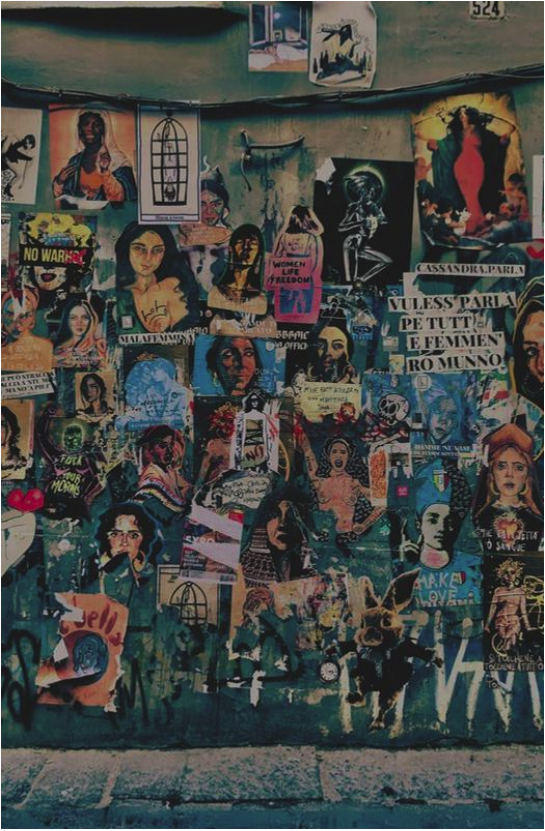

Bleeding Earth

Danielle Nicklas, Clarissa Ren, and Nicole Nicklas

Shantell Powell

The Ghosts of Forests Past

Toxicity in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, Mexico, names a condition where ecological decay and political design converge. This slow violence, born from decades of extractivist expansion and administrative centralization, was inaugurated by a 1967 presidential decree proscribing groundwater extraction by Ben’zaa communities. This juridico-technocratic device reconfigured water from an organizing landscape presence into an object of calculation, converting a hydrological commons animated by ritual into an agricultural expanse for production. In doing so, it subordinated ritual and communal assemblies to managerial abstraction and imposed a monistic rationality upon a plural world.

This register of toxicity is thus more than chemical; it is at once bureaucratic and ontological. It manifests as a slow poisoning of the trust between communities and aquifers, the depletion of collective assemblies, and the silencing of more-than-human entities—such as rain deities and mountain guardians—whose reality persists in situated ecologies of practice (Ulloa 2024). By circulating through institutions and imaginaries, this toxic order recalibrated reality itself, narrowing ontological possibility to a single, normative regime.

Saving Sylvester: Community Responses to Coal Contamination

Noah Dennison

When I first arrived in Sylvester, West Virginia, I met my host in the gravel parking lot of the old motel she’d recently renovated into the town’s first and only Airbnb. The building had been passed down to her by her uncle, she said, and she’d spent the previous year gutting, remodeling, and furnishing its twelve rooms. So far, bookings have been sparse since the Hatfield-McCoy Trail system – a relatively recent and lucrative addition to the southern West Virginian adventure tourism ecosystem – skips right over this part of Boone County. There are a few long-term tenants on the first floor, but the bulk of her out-of-town business is provided by visiting coal industry employees working out their contracts in the nearby Elk Run Complex. I was the first anthropologist she’d hosted.

Kibbutz Gan Barbie

Anna Fine Foer

collage 22”h, 30”w. 2023

After the Israel-Hamas war, a utopian kibbutz was founded with Israeli and Palestinian Barbies. Agricultural production is in the form of charms growing on trees to ward off evil. This collage was made in response to the atrocities of the war after I made a collage depicting the destruction.

The “Kibbutz Gan Barbie” collage relates to hope by imagining a utopian future where coexistence and collaboration transcend the devastation of war. By portraying Israeli and Palestinian Barbies founding a kibbutz, the artwork symbolizes unity and the possibility of peace. The agricultural production of charms that ward off evil represents a communal effort to nurture harmony and protect against further harm. It reframes tragedy into a vision of healing and reconciliation, offering a hopeful perspective amidst the atrocities.

Aina Naval i Cucurella @supervivent_psiquiatria

Against Psychiatric Toxicity: Survivor Voices as Antidotes

The language of “mental health” is everywhere: in social media reels, public policy, wellness campaigns, family conversations, even in the political sphere. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, emotional distress and psychological suffering have become more openly acknowledged, normalized, and discussed. On the surface, this might seem like a collective breakthrough—a necessary opening for care, solidarity, and healing.

But in the shadows of this openness, a deeper, more insidious toxicity hides: he institutionalization and medicalization of human suffering. “Mental health,” as commonly framed, operates as a cultural euphemism for pathologized suffering. It renders complex human experiences into diagnostic labels. It neutralizes resistance, obscures political violence, and individualizes the consequences of collective harm. And perhaps most dangerously, it justifies systemic abuse in the name of care.

Toxicity transcends the chemical realm: it infiltrates institutions, discourse, bodies, and imaginaries. Yet, toxicity can also generate insights, revealing the fractures in our systems and prompting us to envision new pathways.

Ok fine, let’s talk about AI…

Julie Souza

I feel cynical about our relationship with technology. Perhaps the dystopian media I grew up with planted the seeds or the negative effects of having the smartest computer ever created glued to everyone’s hand has encouraged this cynicism. I am fed constant information, sometimes contradicting, about how technology not only impacts humans, but the environment we live in. If I have learned anything about cynicism it’s that it’s normal for it to arise and to navigate it requires open-mindedness and shame-free education. So, let me share what I learned, and I hope we can keep an open mind together…

Caroline Hamilton

Small Stories for #SolarPunkSunday

L1>Peddlers

“A peddler (American English) or pedlar (British English) is a door-to-door and/or vendor of goods.”

Long after That Event, when no one remembered what day it was any more, great caravans of cyclists, or peddlers, would travel along the ancient autobahns, ringing bells, flashing many-coloured lights, playing music, making pizza and electricity, seldom stopping, except to swap a battery for flour. And whenever people gathered to watch them pass by, those days were known as Solarpunk Sundays, though no one remembers why.

Alexandra Duprey

Goddess of Places Forgotten

Burgeoning out of the understory with heavy, velvety leaves, I notice that the tall plant feels defiant in the rocky soil of the hillside. I am at a Zen Buddhist retreat in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia. As we line up outside the old wood-paneled cabin, built decades ago by Quakers, I breathe in the muggy summer air. We do our walking meditation in unison, our palms held in gassho in front of our faces as we breathe together, elbows akimbo.

The leader at the front of the line walks us up and down the drive. The only sounds are soles against gravel, choral cicadas, and the crickets that rise as dusk descends. With each breath, my mind clears, allowing the subtle noises to melt into me as I give my attention to my senses. I can’t help but notice, again, the plant to the side. She stands alone in the balmy Appalachian heat. Her leaves and stalk are both a deep green, a green richer than those leaves of the Tulip Poplar that whirl in a daze to the forest floor, or the swaying long leaves of the nearby Black Walnut tree, branches heavy with loads of fruit.

The wide leaves of this plant stood apart from one another, the layers spaced so dramatically as not to touch at all, each leaf as independent as the plant itself in this wooded landscape. We pass the plant again and again during our walking meditations, each of us half an arm’s length away from one another, yet together like leaves along her stem. Those evenings, the sun dipped down, down, down along the rolling spine of the hillside. Even the sun bows to the Appalachian Mountains, their ancient power stowed in leaf litter and tannin-stained streams. The plant reached up towards the stars and meteors rocketing through the heavens, while the Buddhists dreamed of emptiness.

Editor: Jessie Croteau

Editorial board: Inna Alesina, Lindi Shepard, & Siyu Xie

Responses