Development without Displacement: The Fall 2022 Practicum

The Sustainable Design Practicum gives students at Johns Hopkins University and other local educational institutions the chance to join the collective struggle to build equitable and sustainable urban futures in the city of Baltimore. Taught out of the department of anthropology at Johns Hopkins, each year-long sequence brings together graduate and undergraduate students from diverse fields, all committed to environmental justice and sustainability. In 2022-23, the Practicum is co-taught by community organizer Shashawnda Campbell of the South Baltimore Community Land Trust, and Johns Hopkins anthropologist Anand Pandian. This collaborative blog will tell the story of our work together this year. Stay tuned for weekly updates.

__________

August 31, 2022. It takes a long time to get to Curtis Bay from our university campus, a journey that highlights the longstanding commitment this segregated city has made to keeping its wastes and heavy industrial infrastructure far from its privileged citizens. But poor communities and communities of color live face to face with a noxious reality, including the coal dust that inundated Curtis Bay streets and homes last December when an explosion rocked the massive CSX coal pile looming right over the community.

Shashawnda led us on a walk from the Curtis Bay Rec Center to the nearby piers where coal from West Virginia is loaded for export to Europe, Asia, and elsewhere. These towering heaps of coal to burn, the massive ships that will cart it away, the gargantuan new Amazon warehouse that we kept walking and walking and walking past to get here: the scale of things here is truly daunting, the question of what we can say or do in the face of these developments unsettling.

Shashawnda pointed out the American flag planted proudly beside the coal pile, celebrating the site as a national achievement. “Putting a flag here, in a low-income community of color, it’s like a mockery of them, like saying that they don’t matter in a United States where they should. They say that all lives matter here, but they don’t.” One of the students noticed that the American flag was smudged with gray on account of all the coal dust in the air here, dust that was getting into our own lungs, evidence of a tainted legacy.

– Anand Pandian, Department of Anthropology

__________

September 07, 2022. The air reeked of sewage, a stink thickly felt as it seeped from the wastewater treatment plant and into our vans. A guided tour by Shashawnda of Wagner’s Point and Fairfield brought us to gated parking spaces filled with overgrown grass and transportation trucks, with storage facilities and other buildings towering above us. The overcast sky paralleled the drab gray of the concrete parking lots. Coupled with the scale of these buildings, the area felt at once overwhelming and alienating.

And yet, as Shashawnda revealed, this very same place was once filled with orchards and trees, families and homes. Hidden behind one such gated parking lot, Shashawnda gestured for us to see, was what once was the last house in Fairfield.

In 1912, Wagner’s Point became entangled with industrial waste as the land was sold to oil and chemical companies. Throughout the 20th century, these industries expanded, and “accident” after “accident” forced residents to move away. But as Nicole Fabricant notes in Fighting To Breathe: Race, Toxicity, and the Rise of Youth Activism in Baltimore, these accidents weren’t accidents, but “part of a historic process by which South Baltimore became a dumping ground for the rest of the city: a home for factories, for refuse, and for members of the Black and white ethnic working class.” History continues to repeat itself, as these “accidents” occur in South Baltimore today.

One might associate the word “sacrifice” with “honor.” But as students in our class noted, for communities who live in sacrifice zones, there is little honor in being forcibly pushed out of the communities they had grown up in. There is little honor in sacrificing and erasing bodies, communities, air, and soil for industry, turning spaces filled with homes and memories into mere ghosts of what it once was.

– Bonnie Jin, Department of International Studies

__________

September 14, 2022. Under the dim glow of the slightly eerie “red” church, we settle in the familiar space of our basement HQ. Each of us took our seats at the tables as Shashawnda and Anand explained the activity for the day. They described a grand plan–to build our dream communities using the materials they’d allocate (Legos and magnetic blocks), while they took up new personas for themselves: Mayor, City Councilmember, Policeman (morals unknown). And so, community development and building commenced!

The going was hectic as all of us at each of the three tables discussed, assembled, and organized our communities with whatever resources, ideas, and funding we were given by our – at times generous and at times abominable – mayor. Each community took what they were given and created what they could, from a completely green diaper incinerating plant to a communal fridge. In the process, there were talks of a coup, of mutual aid, and of how resources were being stolen. By the end, we ended up with three drastically different communities with asymmetrical resource and development capabilities that were reminiscent of some of the neighborhoods in the city of Baltimore.

Why is it that some spaces are robbed of opportunities to grow and flourish, while some are stuck in a stagnancy not unlike dangling on the middle rungs of a ladder, while even others are constantly on the up-and-up? Where are resources coming from, and where are they going to? Questions like these floated around, as we arrived at a working understanding that different spaces have different memories, experiences, and sentiments of development, often without being able to fully articulate these experiences to each other. At the same time, a large part of the responsibility for creating asymmetric communities lies with the state. In this simulation, many of us clashed with the leaders of the city to express our discontent–at the gap between the actions taken by the leaders, and the obligations expected of such leaders to promote a better, healthier, and life-sustaining city.

We ended the class with a tour of some plots of land that the SBCLT has acquired in south Baltimore, for a real-life example of some of the ways that communities have come up with solutions to unjust patterns. Plots of land waiting for newly erected houses, chessboard columns made of stone, hand-painted garbage/recycling/composting signs, and a hand-built stage all become the inchoate signs of reclamation, as a community comes together to carve out new, meaningful spaces for life.

– Lucy Chen, Department of Anthropology

__________

September 21, 2022. We drove down to our basement HQ with a significant agenda in mind. Today was our day to share back what we had learned from our first round of research based on specific incidents we had picked out from a timeline about environmental hazards in Curtis Bay. We arranged our chairs in a circle and grabbed some post-its to write down a brief one-word summary of the incident we had picked. Our circle was reminiscent of a storytelling circle (usually around a fire) — and perhaps we were doing that by piecing together parts of the story of, “Why is South Baltimore so polluted?”

Each of us talked in detail about what we had dug up from different sources to shed more light on the different incidents. The conversations we had were heavy, angering, and dark. The long lineage of irresponsibility and injustice — chemical spills, toxic waste dumping, explosions, chemical warfare — there were too many — and there was too much leeway given for this to continue happening.

Towards the end of the class, we walked over to a nearby playing field. Shashawnda mentioned that this was built as a “contribution” to the school and neighborhood by one of the companies around. We looked around, observed and collected different materials, creating a joint story about the field — how the inside of the field was maintained well, versus the outside which was overgrown, littered, and lacking even a sidewalk to go towards the field. This was a parallel for us going back to our own research — we’ve got to look at it from different angles, maybe observe things in the periphery, connect seemingly disparate pieces to create a full picture.

Over the past few weeks, we have been present at either the Curtis Bay Recreation Center, or the church at Brooklyn, with field trips and walks around the different parts of this neighborhood, which has connected the text to the tangible. Our collective research is not just about understanding the context, the atrocities, and the injustices that have occurred in South Baltimore — but also about building an archive of evidence, an exposé for things that have slipped under the radar. It is our treatise to and for South Baltimore, to hold leaders, industries, and people in positions of power accountable.

– Jigyasa Tuli, Social Design at Maryland Institute College of Art

__________

September 28, 2022. This week, we had a special visitor to class – Dr. Nicole Fabricant, professor of anthropology at Towson University and author of the forthcoming Fighting to Breathe, a story of environmental racism, pollution in South Baltimore, and the youth activists fighting against it. It’s easy to tell Dr. Fabricant, or Niki, is a teacher. Almost immediately after we arrived at the church, Niki handed us fact sheets about Grace Chemicals, one of the many polluting companies on the industrialized peninsula of Fairfield. On a Wednesday at 5pm during midterm season, Niki’s energy is impressive, something to behold. I’m sure much of what she showed and told us about the toxic industry of Curtis Bay is old hat for her, but it didn’t seem old hat as she gestured wildly, raised her voice at all the key moments, looked us in the eyes.

We drove our vans through the peninsula. The first site Niki wanted to show us was fenced off to the public, not uncommon here, so we changed course and moved on.

Eventually we found ourselves in an open parking lot at the Solvay USA visitor center. We got out, stretched our legs, and almost immediately had eyes on us. Not long after, a couple of Solvay employees came out and asked what we were up to. It was a completely pleasant exchange; we were not asked to leave and in fact Anand was able to get an email address so that we might get a tour. It was clear, however, the worker was unsettled by our group: “You get nervous when you see a group like this,” he laughed, “especially outside of a chemical plant.” We smiled and nodded along, staying agreeable.

Later, Anand mentioned that the group of employees was eager to point out their Baltimore Checkerspot habitat garden in the front of the building. As we drove away, I glanced out the van’s window and saw a cluster of bushes no taller than a small child in an area you could cover in 4 or 5 strides. Blink and you’ll miss this patch of green among the swarm of built structures, the fields of concrete, the angry buzzing of diesel trucks flying past.

The Baltimore Checkerspot Butterfly. Photo by Judy Gallagher.

Back at the church, we were able to keep Niki a little longer and pepper her with questions about her book and her work in South Baltimore. We spoke about extractive versus participatory methods of research and ways of being. We spoke about tokenism in historically marginalized communities of color. The narratives of poverty and race we gravitate towards are often the easy ones, pathologizing Blackness and reinforcing deficit thinking. But what makes stories good ones are the unique, often complicated, details.

In my discipline of education, QuantCrit is one answer to the problem of reductive research practices. Among its many tenets, QuanCrit holds that numbers are not neutral, and data cannot speak for itself. Benjamin Franklin High School’s test scores, Curtis Bay’s median income, Fairfield’s air quality index, and South Baltimore’s racial demographics are disembodied numbers, meaningless without the work of organizations like the South Baltimore Land Trust.

On stories and the power of narrative, Niki made sure to remind us that her work with Free Your Voice, or the environmental justice class she teaches at Benjamin Franklin, is not the Hollywood-ready story of ‘at-risk’ youth who overcome the odds and change the world. Yes, there are small wins, but it’s hard, bumpy work along the way. In the end, it’s the fight that keeps them going.

– Lisa Nehring, School of Education

__________

October 5, 2022. The drive to Curtis Bay is familiar as we trace our way towards Station North, past Camden Yards, and eventually into South Baltimore. We come to what a few of us have affectionately named the “red church,” given the color of the warm light streaming through the windows. We meet a few community organizers there and, for the next 45 minutes, have the pleasure of hearing from them about their past work in the community and what they envision in the future. It is a privilege to hear from them: their hope and resilience are an important reminder of why this class exists and how lucky we are to learn from such incredible people.

I clearly remember the first few times we visited South Baltimore and how we were collectively stunned at the sheer scale of the industry. Professor Pandian often remarked that the area was not built at the human scale, and this discordance was reflected in some students’ despair. To us, relatively new to community organizing at any scale, the sheer magnitude of the industry and pollution and political order, in a sense, the magnitude of the environmental racism at work, seemed insurmountable. We were reminded that sentiments like this are part of why areas like Curtis Bay are deemed “sacrifice zones,” areas that have become so polluted they seem unsalvageable.

Today, hearing from three community organizers: Miss Edith, Meleny Thomas, and Ray Conaway, committed to the fight to save these neighborhoods, was a humbling experience. Each has taken different routes in their fight. While emphasizing the importance of staying in the community and fighting for it, Meleny spoke about optimism and self-reliance as organizers wade into unfamiliar waters (like property law), and Ray uses his political platform to educate community members and facilitate effective communication. Compared to our earlier thoughts about the seeming futility of the fight, their continued commitment, optimism, and resilience were a reminder of the strength of the bonds of community and a crucial reminder of the fact that Curtis Bay is, first and foremost, a home to many people. Though industry has done its best to change that, even a rezoning to heavy industry has not erased the neighborhood’s character.

The class closed with a general discussion of where we want to go in the next few months. After so much research into the question of why South Baltimore is so polluted, and after hearing from residents, there was a collective urge to investigate the inverse: what is the history of the struggles against pollution? Speaking to the organizers was an important reminder of our role in the first half of this class: to collectively work to build up an archive of knowledge that would hopefully be useful in the fight. On the van ride back to Homewood, we traced our path over the Hanover Bridge, the very same that Ray referenced as he spoke about his childhood commute from home to middle school and back, where he saw, before his eyes, the disparity of resource availability between South Baltimore and Federal Hill.

The struggle against pollution in South Baltimore has, generally, not been well documented in traditional academic literature or political discourse. Still, it exists in beautiful detail in the lived experience of long-time residents. One of the struggles many of us have noticed in anthropology is legitimizing non-archival and non “textbook” research. By prioritizing community members’ oral histories and perspectives over traditional theory and peer-reviewed works, we may be able to push the boundaries of traditional anthropology. By doing so, we may broaden the field for the better, rendering it more useful in South Baltimore’s fight to save its home.

– Larkin Gallup, Department of Anthropology

__________

October 12, 2022. “Community”, as she expressed, drew Sarah of Hon’s Honey to Curtis Bay. We joined her and a team of wonderful women only a few minutes’ walk from the Curtis Bay Recreation Center, her sentiment shared and mirrored in our stances as we leaned on the tips of our toes, eager to volunteer.

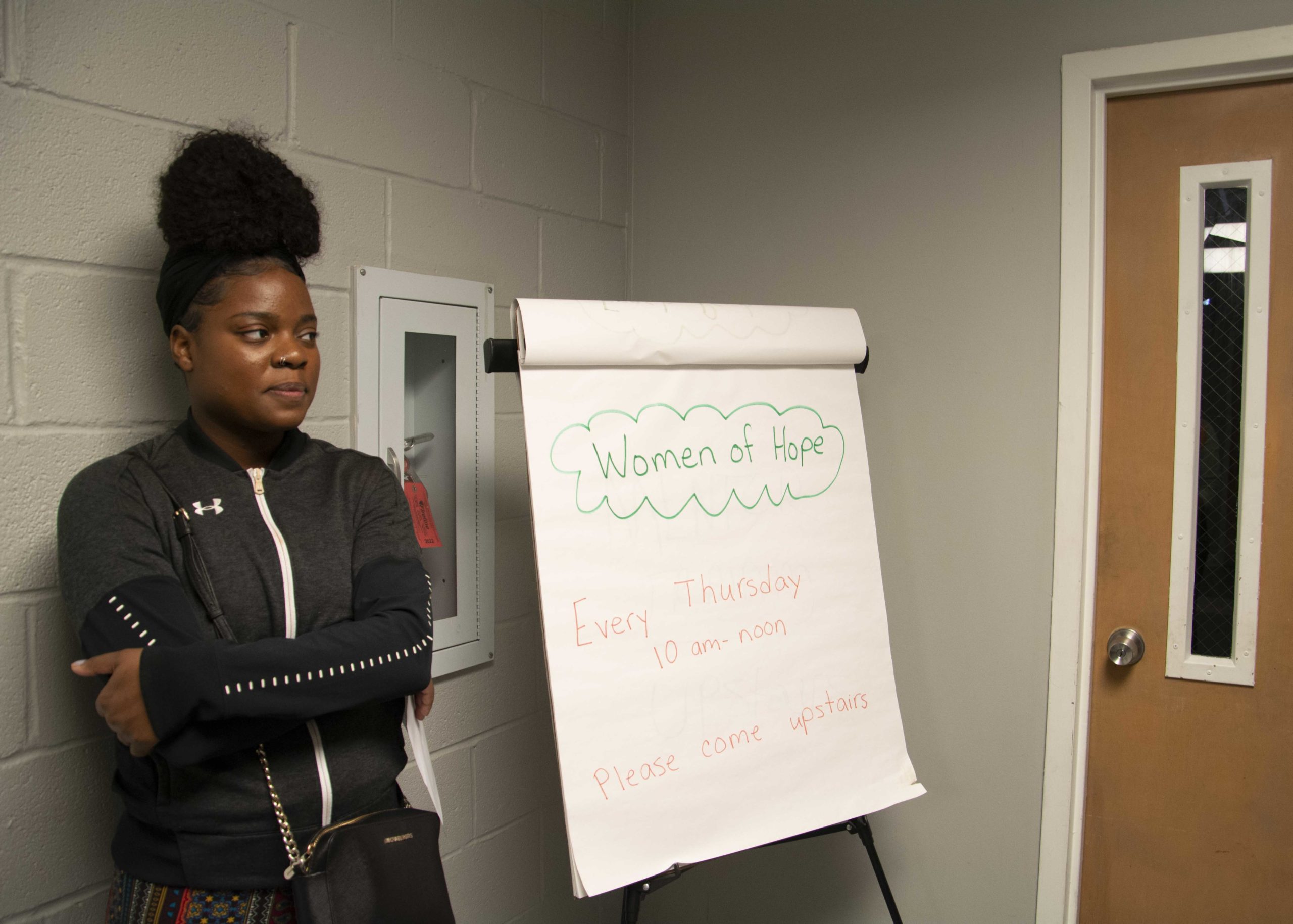

The soft, eclectic array of candle scents and soap aromas pooled around the entrance to the space, dispersing until unrecognizable in the air. Sarah Batley, Senior Director of Hon’s Honey, briefly led us through the inspiration behind the program and the communal themes that drive her work in South Baltimore. Hon’s Honey is an employment program with The Well, a space for women in Baltimore who have survived abuse, carried trauma, and have since been in search of communal healing.

Of the 12,000 jars of sweet, viscous honey needing to be prepared, our packing team managed 858 sealed and ready. Between us, the litter team collected 5 bags worth of litter from the surrounding blocks, sharing a sense of pride in the fullness of our bags that, upon a momentary pause, devolved into a solemn aftertaste. The windows were clearer when we returned, an endeavor on two fronts as teams from the inside and the outside wiped the glass clean. On the walk back to the Community Center I stared down the scraps that littered the gutters beside the sidewalk, wanting to lift each butt and bag from the earth and wishing that one day I wouldn’t need to. A couple of us shared knowing glances and cynical grins upon hearing that CSX itself lends trucks to the community cleanup efforts.

Back at the Center, in a warm room on small chairs that kept us close to the ground, we debriefed our volunteer session and delved into our reflections of the CSX explosion court hearing. Merely distinguishing between those who were present at the hearing and those who were not, as we shared, can express the thematic discord between concerned community members and ambivalent industrial or government representatives. Videos sharing community accounts of resident’s experiences living within a sonorous radius of the plant were poignant, powerful, and undeniable. One resident swiped a finger along the wall of their home, coming away with a pitch fingertip; the window troupe were unsurprised, yet no less dismayed when they cleaned the windows of the Well to find this very soot on the wipes they used. There is nothing more real than a lived experience.

Outside the Well, a quote tattooed on Alaa’s left forearm caught my eye as she lifted her bag bulging with litter, dropping it inside the dumpster. She translated the line to, “you’re forgotten as if you never were“, from Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish’s namesake poem.

Curtis Bay is a “forgotten zipcode” Sarah said, where homes are a 3-hour round-trip from a chance to restock their fridges but an evening stroll away from a colossal coal pier. Its history and its heritage was wiped clean – or, more aptly, buried beneath a layer of coal and construction dust.

But even as the soothing scents of soap secede into the neighborhood, they pervade the air. Though we don’t see it yet, change is coming slowly, and today it took the form of concentrated acts of genuine service. As we enter the next phase of the practicum, it will find itself in the knowledge we source and the resources we design. In time, community will prevail.

– Mansha Kapur, Department of Physics and Astronomy

__________

October 19, 2022 This week our class met virtually using the EDC’s video room feature. We were a little bummed to not be meeting in Curtis Bay but were happy to connect and have some generative conversation.

We started class by discussing the book Essentials of Critical Participatory Action Research by Michelle Fine and María Elena Torre. Critical Participatory Action Research refers to research rooted in social theories that examine inequity and structures of violence (Critical) in a way that is democratic and centers the knowledge of those who are most impacted (Participatory) and connected to social policy, legal reform, organizing, creating art, etc (Action). We talked about the importance of co-learning and building knowledge in collectives (between those in the academy and communities historically excluded) and while we were a little skeptical about the accessibility of the writing in this book, we found the questions it posed very applicable to our work in this class.

Specifically, we are thinking about how to create collective spaces. In the context of our class, we recognize that while thinking about the harm caused by industry in Curtis Bay is a choice for us, it is a constant reality for the residents. As a result of this, our research should be accountable, not to the academy, but to the community. As we continue with our research, we need to make space to reflect critically on our work and consider how we might design it better. We closed our discussion with an examination of “what kinds of evidence are needed to provoke wide-awakenings” and how we can frame our findings in ways that contribute to action to address ongoing harm in Curtis Bay.

– Arunika Bhatia, Department of Environmental Health & Engineering

__________

October 26, 2022

There were two narratives taken today. The first was Ms. K, who is a witness and survivor of the coal explosion, and the second was Ms. M. We met both of them at the Rec Center.

Ms. K started by narrating her own personal experience of the coal explosion. She has lived in the community for 24 years. She comments on how the smell of coal is always lingering. She constantly asks what she is smelling, and this is usually the lingering effect of the coal. She has considered moving, but she likes where she is because it was close to her work and she likes the people. Not to mention that the idea of home and belonging is important for her, since she was brought up right across the street.

On the day of the explosion, she heard a massive sound – “boom” – as though a truck hit the building. Her coworkers came running to check on her, and they went out to look around and see what happened, only to look at each other’s faces and find them filled with dispersed coal. Ms. K showed around a picture of herself on the day of the explosion. “Windows were busted out, everything was black. My car was white, and my son’s raincoat too… They all became black from the coal all over,” says Ms. K. She narrated how she decided to go to the hospital to check on her lungs; after all, a coal explosion might have caused severe injuries without her necessarily feeling it due to the effect of the event.

We also met Ms. M, who spoke about how breathing is a luxury in this community. Her son, like many, had his asthma worsen significantly here. “His breathing was so bad, although I am a clean freak, but there is only so much I can do,” she explained.

Both narratives touch on the problem of environmental degradation, but also re-draw the relationship between the outside (coal and pollution) and the inside (homelessness). Here, the “environment” is a broader ecology, a set of relations that includes the natural and built environments in a constant relationship with humans and non-humans. Environmental (in)justice and social (in)justice cross over and are never really one or the other, and that is resonant with the fact that you cannot bring up youth crime, without bringing up homelessness and discrimination simultaneously.

– Alaa Saad, Department of Anthropology

__________

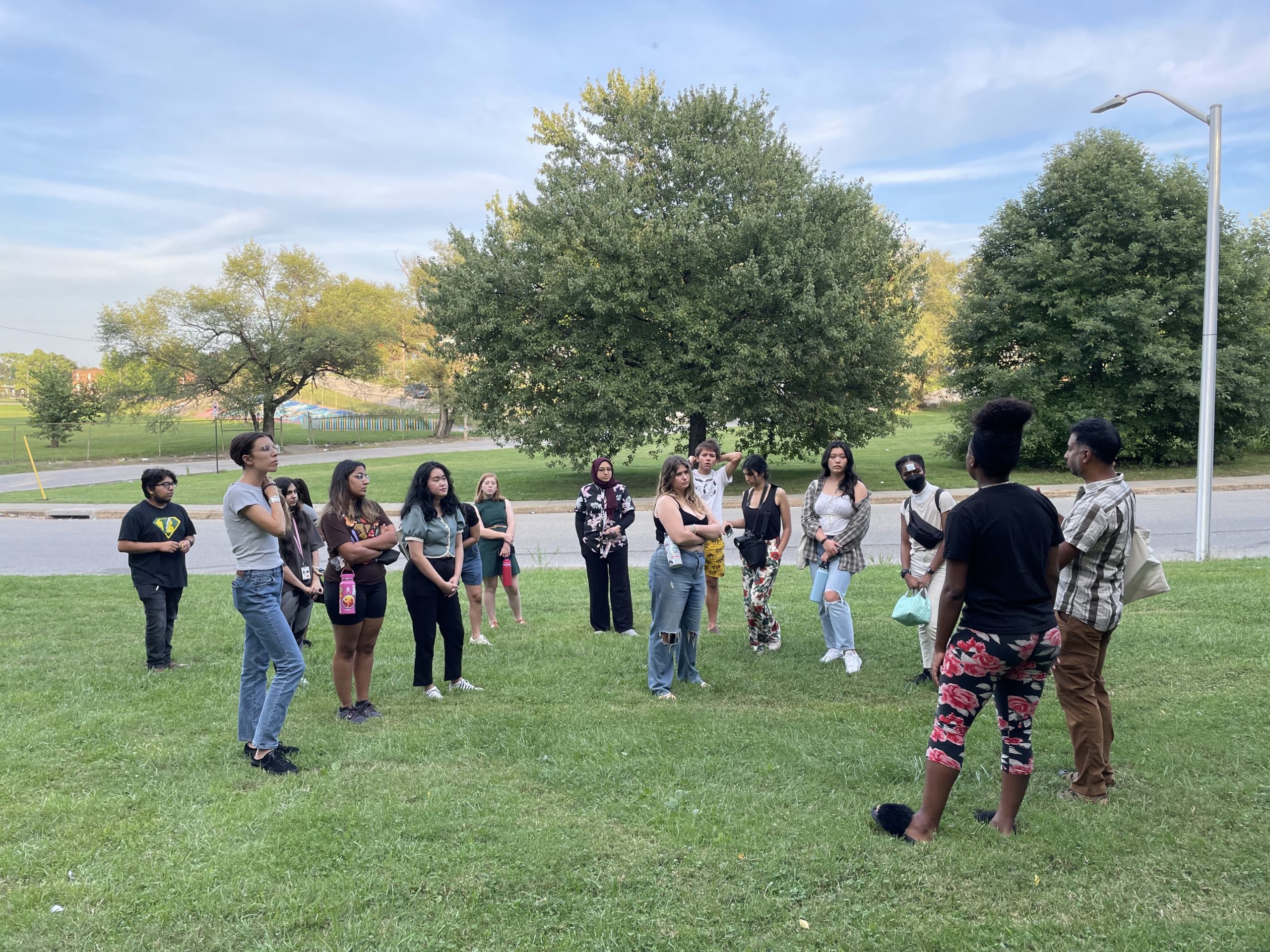

November 2, 2022. This week’s class revolved around action. We did a canvassing workshop with the South Baltimore Community Land Trust (SBCLT), led by Shashawnda Campbell, Dr. Nicole Fabricant, and Raychel Gadson, a JHU graduate student and previous member of the Sustainable Design Practicum. We were also joined by students from Towson University and University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Shashawnda led us through the importance and necessity of canvassing as a way to rally communities and gather their invaluable input, followed by a very informative and comedic skit to see the process in action. Then, we used her canvassing script and practiced with partners so we would be prepared to volunteer over the next few weeks. This class felt like a shift from the discussion-based nature of many of our other classes, and it was exciting to learn that we can apply all that we’ve learned over this past semester to help bring the community together and support much-needed organizations like SBCLT.

The workshop was a safe and welcoming space, too, for questions about the work and our place in it. Some of us expressed feelings of hesitation or discomfort around asking people to relay their experiences with such a horrible and traumatic event to some random college students outside the community, and I think this discomfort is important to keep in mind when talking to residents, as we relay information and listen for their experiences. However, the fact of the matter is that SBCLT needs people to help, and we can provide it. Attentive listening, understanding, and connection is so key for doing this work respectfully, and the mission of informing and uniting a community is far larger than our concerns.

It was reassuring to hear Raychel admit that she had never intended to canvas, that she had planned at first to sit it out when she was in our shoes in her own practicum class due to discomfort. Knowing that she went from that place to where she is now, teaching us how to do the very thing that once terrified her, was inspiring. It’s scary to knock on random doors to talk about such a heavy subject, with no knowledge of how your message will be received, but it’s reassuring to know that the leaders in the area were once beginners, too. Overall, it made canvassing and environmental justice work feel more accessible and open, rather than daunting.

– Layla Salomon, Departments of Cognitive Science and Environmental Studies

__________

November 16, 2022. Plenty of times we had walked around Curtis Bay, careful to not disrupt people as they relaxed on their porches. Today, that changed.

On November 30th, the Curtis Bay Community Association is holding a rally for Curtis Bay residents to air out their grievances regarding the nearby CSX coal pile and its explosion in December 2021. Some of us had worked on creating a flyer to hand out to inform people of the event. Shashawnda had emphasized to us previously that residents often preferred a more face-to-face approach to communication, so today the class geared up in winter coats, grabbed our clipboards, and headed out onto the streets of Curtis Bay. Shashawnda walked us through which blocks we would be canvassing before letting us go out in small groups. Within seconds the street would be filled with students knocking on doors to say “Hi, we’re with the Curtis Bay Community Association.” If there was no response we would tape up a flyer and leave. For the next hour, we canvassed the streets before returning to the Curtis Bay recreation center.

Although I did not personally speak with someone, my classmates were able to share their experiences of talking with residents. Some students talked about how pleasant some of the residents they spoke with were. Others were surprised that they had encountered residents with racist prejudices. Some residents gave detailed recounts of the coal explosion, while some simply said “it went boom.” Regardless of how the message was told, the same sentiments underscored each encounter: frustration, fear, and worry. Sharing residents’ stories emphasized for us the importance of the work we are doing. Energy levels were high as we discussed what we had done so far and what was left to be done, even into the New Year.

On the drive back to campus, we talked further about how excited we were to help Curtis Bay residents bring about change. Anand mentioned how grateful he was for an interview I had done with The JHU Newsletter about the class. My interview, he said, allowed him to show the university that there is interest among students to work with Baltimore residents and bring about change. While the work we do may not make a difference on our CV or provide us a senior thesis, it helps strengthen the Curtis Bay fight. The fight for better treatment. The fight to live healthily. The fight to be seen.

– Tomisin Longe, Departments of Anthropology and Psychology

______

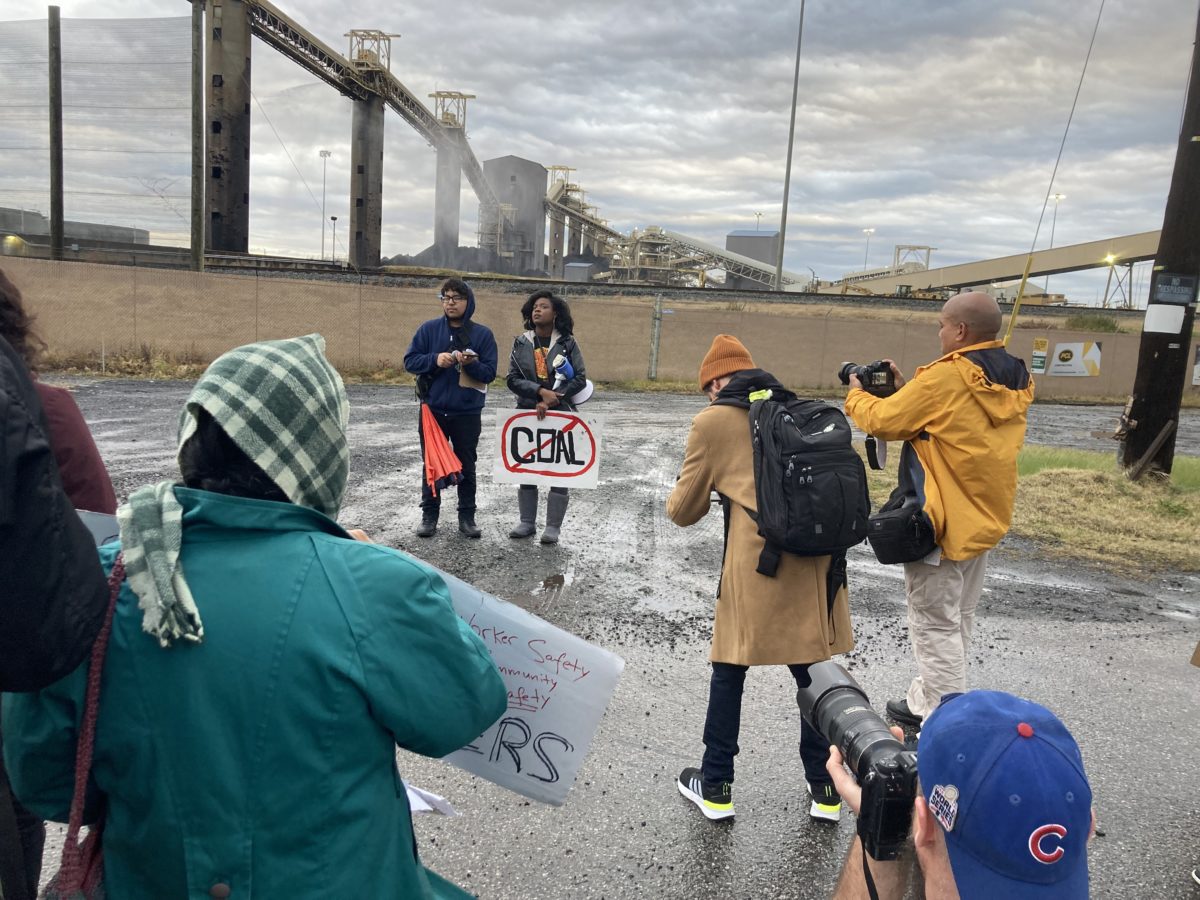

November 30th, 2022. Almost exactly 3 months ago, our class followed Shashawnda on a walk down Curtis Ave., all the way to the gates of the CSX coal pile facility. This walk was marked by a sort of morbid curiosity, if not awe, at the towering mass, and silence. Who were we to approach this monster?

Today, fittingly, we repeated this walk. Yet our experience was vastly different. Today we walked with the community of Curtis Bay. Today we walked with friends and supporters of Curtis Bay. Today we walked with believers in a better Baltimore. Today marked the first march on CSX in wake of the December 2021 coal explosion.

Organized primarily by Shashawnda, the protest began at the Curtis Bay Recreation Center. Here gathered community members, allies, and representatives from most of Baltimore’s local newspapers. From there, it headed south on Curtis Ave., past rows of empty warehouses, then east on Benhill Ave., until the road’s end at CSX’s gates. We chanted and yelled the whole way to and from the facility to the tune of “Hey! Ho! CSX has got to go!” and “No justice! No peace!”, and heard the first of our testimonies from community residents. Unlike our first walk, there was no awe, no silence. This walk was characterized by the passion of people fighting for the future of their community. We concluded our march back at the rec center, where more residents testified to their experience in wake of the CSX explosion, and other community activists spoke, speaking both to protestors and almost more importantly, into the cameras and notepads of gathered press.

This beginning of a mobilization against CSX seems to very much highlight a marked change in our class since August. Our work has eclipsed that of a typical classroom, demanding we do more than just be academics. I cannot speak for my peers, but the more time we’ve invested in this community, the more my outrage about the history of environmental injustice in Baltimore, particularly Curtis Bay, grows. The mishaps of industry in South Baltimore are not isolated, harmless incidents. People live here. Families grow up here. To fail to act is to be complicit in this “slow violence”.

However, it would be naive not to acknowledge the inherent risk associated with activism. We closed class with a more serious conversation regarding safety and an incident at the end of the protest, where a protester (not from our class) was hit by a paintball in a drive-by incident and had to be taken to the hospital. I also had a chance to speak to other activists at the protest who are facing jail time or other consequences as a result of civil disobedience. It is a privilege to be able to assume risk in the name of advocacy. We are doing real, productive work in support of activism in Curtis Bay, but real work can have real consequences.

Some of the press coverage about the protest can be found below:

The Baltimore Sun, photo gallery

– Valdis Slokenbergs, Department of Physics and Astronomy

Photo by Lisa Nehring

______

December 7, 2022. Today we rode down to the Curtis Bay Rec Center for the last class of the semester. We were joined virtually by KT Andresky, an organizer in Detroit working with the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives and Breathe Free Detroit. KT told us about her community’s successful campaign to shut down the incinerator in their backyard. She told us about all of the additional tools and resources they created to support the community and the plant’s workers once the incinerator was closed. Her work thrived in a space of creativity, adaptability, and humility. Her talk highlighted how environmental justice intersects with many other justice movements like housing, workers rights, and healthcare. Her work showed how important it is to approach environmental justice with a community-first mindset so that local residents can remain in place and thrive in the communities and neighborhoods that they fought for.

While we were talking with KT, the class was also working on a project we started at the beginning of the semester. For this project, we had each researched a historical environmental hazard event in south Baltimore from a timeline that highlights the continued pollution and destruction of local communities and the air, land, and water around them. The class did an amazing job researching and tracking down more information about events within the timeline. This week, we worked with Krishnan Vasudevan, a journalism professor at UMD, to make audio recordings of the research pieces we wrote with our voices and the voices of community members and activists. We hope the video we’re making can be used as a tool for South Baltimore Community Land Trust and others to highlight the systemic injustices inflicted on the people and land of South Baltimore.

It is hard to believe that today was the last class of the semester. As cliché as it sounds, it has been a great honor and privilege to be invited into this space with Shashawnda Campbell, the South Baltimore Community Land Trust, Curtis Bay residents, as well as local and national environmental activists. While this is a stopping point for us as students, as we all take time to rest and reset during the holiday break, it is in no way a stopping point for the environmental justice work in Curtis Bay and South Baltimore. Yes, this class will continue in the spring semester. However, the goals of this work do not fall within the constraints or limitations of an academic calendar or a project plan. Like KT taught us earlier in the class, environmental justice and community work do not have comprehensive conclusions. Environmental justice is ever-changing and growing to best benefit the communities concerned. The community of Curtis Bay and others in South Baltimore are living with CSX and other polluting industries in their neighborhood every day, literally in the air they breathe. We leave this semester with a better understanding of, and a great respect for, the community fighting hard for a just and healthy future for south Baltimore. We are grateful to have been invited to join the fight with them. We can’t wait to continue the work and learn more together.

– Alice Weston, Social Design at Maryland Institute and College of Art

[…] of our work together this spring, which builds on the work we did together last fall through the Sustainable Design Practicum. Stay tuned for weekly […]

[…] of neighborhood homes, one that refuses to be ignored. Over the last year, students in the Environmental Justice Workshop – a practicum co-taught by community organizer Shashawnda Campbell (South Baltimore Community […]