Climate Imaginarium

Public Display

Public Display

Active 3 months ago

We leverage storytelling for a regenerative future.

The Climate Imaginarium is a center for climate,... View more

Public Display

Group Description

We leverage storytelling for a regenerative future.

The Climate Imaginarium is a center for climate, community, and culture, operated by a coalition of universities, cultural institutions, media organizations, and arts nonprofits.

In 2025, the Climate Imaginarium will produce dynamic cultural programming to complement and amplify the breadth of climate solutions on Governors Island.

Through collective visioning and radical imagination, the Climate Imaginarium will feature exhibitions, performances, film screenings, immersive experiences, and events in alignment with five core themes: climate storytelling, climate emotions, climate literacy, climate justice, and social connection.

Through strategic partnerships, public programming, community engagement, and producorial support, the Climate Imaginarium will continue to cultivate a cultural destination on Governors Island for New York City’s burgeoning green economy.

We’re germinating a regenerative culture and sowing seeds for collective liberation. Let’s dream a better future together.

Learn More | iPhone app | Android app

Share your climate story!

Tagged: Climate Change, Education, Mississippi, Nature, Racial disparities, Snowfall

-

Share your climate story!

Posted by Josh on November 10, 2023 at 12:59 pmDo you have a climate story to share? A poem, drawing, song, editorial, film, meditation, or performance?

Please feel free to share your climate stories — of all mediums, modalities, styles, and genres — with the community!

You can review our public library for climate futures for inspiration.

Jonas Johnson replied 2 years, 3 months ago 4 Members · 3 Replies -

3 Replies

-

The workshop with Jason Davis this afternoon was amazing. The prompts brought a story to mind.

My name is Anand and I’m from Baltimore. I haven’t always been from Baltimore; my family is from south India and I grew up in California. My wife and I moved here for work about fifteen years ago now, but our kids were born here, we’ve lived in the same house and walked the same sidewalks and trails through the woods for many years now, and over these years in our adopted home, no longer quite as newcomers, we’ve also come to see what change feels like on the ground and in the air.

I remember so vividly what happened one winter at Lake Roland, a few miles north of where we live in the city. I’d gone out there one afternoon with my son and daughter to walk one of trails around the reservoir, built more than a century ago. It was a really cold winter, or at least an intense cold snap in the midst of that winter, and the lake had frozen over, had mostly become a flat sheet of ice. This may have happened a lot in the past, I don’t know. But it was a big deal that year, people were talking about it, and we went to take a look.

We spent a lot of time that afternoon just throwing things across the water: small branches, rocks, and whatever else seemed to have enough mass to launch well across the ice. The ice was thicker in some places, thinner than others, and the way that the sound changed while these things sped across the ice, the shifting tone of that resonance and reverberation through the air across and the ice and water below, it was amazing to take it, it felt musical, that vibration, in itself.

But all of this is just a prelude to what I wanted to share, a moment that I hope never to forget. As we rounded a bend around that small lake, picking our way carefully through the frozen earth hidden under the crisp fallen leaves, we were startled by the sight of a movement across the ice that had nothing to do with our antics. Two foxes had appeared all at once on the ice, one chasing the other across the wide span of the lake, racing across that white expanse then disappearing into the brown trees beyond.

The sight of them was a marvel. The fact that they too could move so easily across the ice was riveting to us. The freedom in that movement, the effortlessness of their passage across the ice, that too was gripping somehow, so unlike our tedious tromping down that frozen trail.

This is a story about ice and cold, not about fire and heat. But I think that my recollection of that moment is tinged deeply with a sense of how precarious the simple fact of winter has become, the very idea of that season. Because so much of our time together in the winter, my children and I, has been about the unusual wonders of those months: sledding down the small hill down the road from our house, throwing balls of snow at each other in cackling fits of running and stumbling through the those winter heaps, even the work of having to scrape and shovel the sidewalks together. Nothing to take for granted here, anymore.

The uncertainty that begins to set in every year, this time of year: What will it be like? Will we have a real winter? Will we have snow? Those foxes on the ice spoke to the hope in all those questions, somehow.

-

Tides of Endurance

Tranquil lake/ Seafolk fisherman/ Woven Nets/ Cradled dreams

Ascending tides/ Drifting time/ Depleting Waters/ Pillaging livelihoods

Life to blood/ Fish to death/ Body to silhouettes/ Care to neglect

Fish perish/ Inhabitation chokes/ Once fertile/ Now barren

Shadowed skies/ Insatiable greed/ Leaving behind/ A desolate wasteland

-

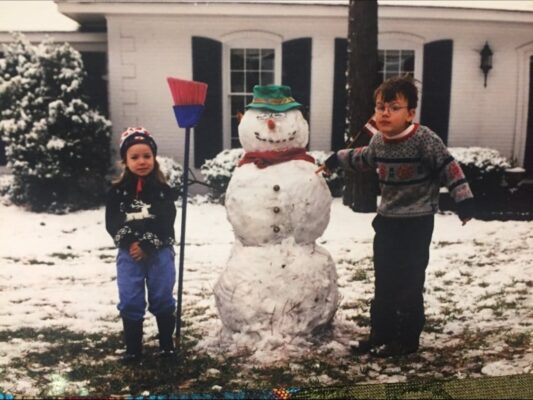

Growing up in southern Mississippi, I have distinct memories of my first snow, which in my city fell once every five or so years. I was maybe six, and I ran outside on a crisp night—along with damn near every kid on the block—to recreate every winter wonderland scene from the library of movies, tv shows, and cartoons that enchanted us every Christmas. I had a laundry list to get through before the two or so inches of snow melted: Catching a snowflake on my tongue, snow angels, snowball fights, a short, makeshift sleigh-ride down an already-slushy hill. By the next morning, each house had an exceptionally dirty snowman (there really was not nearly enough to build the frosty-white guardians of our dreams) keeping watch over the quickly melting blanket of snow that had so mystified us the night before.

—

I didn’t think about this again until I returned from my undergraduate studies in New England (where snow very quickly lost its charm) to teach high school students in the rural Mississippi Delta. The winters had gotten both progressively warmer, and the weather more erratic. On several days my classes were disrupted by torrential rains and flooding—exacerbated by the expansive monocropping of the Mississippi floodplain, which a century prior had turned swamps and bayous into farmland. Empty desks made it strikingly obvious, from my position at the front of the class, behind the podium, exactly which student’s bus routes—and in some tragic cases, entire houses—were washed away by the flooding: the children of Black farmers and laborers made vulnerable by the confluence of climate change and the entrenched racism of Southern infrastructural planning and design.

When the weather did turn cold, it turned angry: an ice storm and frozen roads in January forced school closures for five bitterly cold days. I lounged around sequestered at home, comfy and somewhat relieved by an unexpectedly extended winter break—but an unsettling thought slipped between sips of hot cider and cocoa—I thought of these same students, many of whom relied on school for a hot meal and a stable environment. The iced-over roads and downed tree limbs provided no respite: They could not even take refuge in the simple pleasures of a Home Alone cinematic snowfall, the way I did all those years ago in suburban southern Mississippi.

—

I recognize that the precarity that my students experienced at the hands of an unstable and wildly oscillating climate is representative of catastrophes accumulating across the globe: Rising seas displacing villages in their thousands; wildfires blocking out the sun; extreme heat and unprecedented storms taxing the power grid to the brink of failure; geopolitical tensions boiling over as ecological collapse is internalized as a pressing military—but not social or economic—concern. But these experiences hammered home for me a less lethal, but no less devastating reality: as these crises accelerate, a relationship with the natural world marked by childlike wonder melts away like those rarified Mississippi snowflakes, replaced by the icy sting of pain, suffering, and displacement—”Nature” becomes a foreboding term. How can we expect a rising generation to grow into stewards of a shared world, when that world constantly presents itself as a spiteful presence, exacting revenge for sins distributed across time and space, punishing those least responsible for the willful negligence of profiteers?

Another painful memory, only a few weeks into my time as a teacher, serves as a haunting reminder of the cruel disparities wrought by our fearful negligence of nature, above and beyond the climate crisis. On a beautiful, sunny afternoon, the principal announced over the intercom that all teachers must immediately draw their blinds, and that no students should be released from class for the next hour. A rare solar eclipse—by all accounts, a once-in-a-lifetime cosmic experience—was passing over our small city; the administration, unlike other districts able to secure sets eclipse safety glasses, directed us instead to protect students’ vision by restricting their movement. I felt so helpless, reluctantly standing guard over my classroom—and angry at the school and at my own lack of foresight.

As I futzed with my projector to open up a livestream—a pitiful replacement—the intercom cracked back to life. One by one, a handful of students were called to the office for early release; their parents had taken off work early to shepherd them, eclipse goggles in hand, to marvel at the natural world. I watched them leave, giddy with excitement; all of them white, middle class students of the majority-minority public school. Just five years earlier, I would have without a doubt tread the same re-segregated route down the hallway, greeted by enthusiastic parents with flexible schedules and disposable incomes, a privileged recipient of yet another “enrichment” activity. As the totality passed, I watched my remaining students glance wistfully towards the cracks in the blinds, a passing shadow and a pixelated projection the only trace of the event.

—

I returned home that day deeply unsettled and dispirited, until my roommate, Phil—who taught at the elementary school down the road—waltzed in beaming, recounting a quite different experience. One of his students’ parents worked at an auto-body shop as a mechanic, and had brought in a huge, polarized, UV-tinted truck windshield, which functionally operated as a massive eclipse looking-glass. The entire class took a brief field trip to the playground, where they crowded around the windshield; Phil’s eyes sparkled as he recounted kids pointing and peering out at the sun, his experience of the students’ wonder and excitement eclipsing the event itself. Amidst the catastrophic failures of our institutions, this second-hand story fosters an abiding faith in the resourcefulness, thoughtfulness, and initiative that our communities can muster—and reinvigorates our collective duty to rekindle imaginations at scales small and large.

Log in to reply.