Jonas Johnson

Forum Replies Created

-

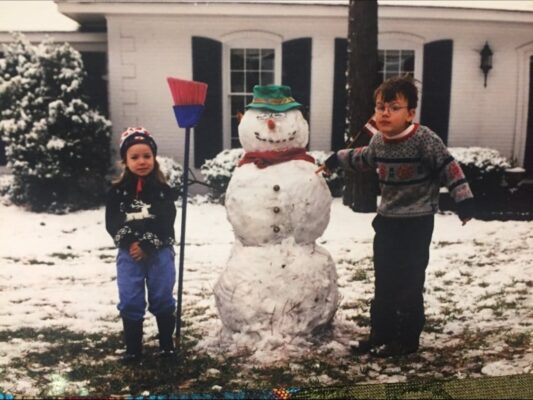

Growing up in southern Mississippi, I have distinct memories of my first snow, which in my city fell once every five or so years. I was maybe six, and I ran outside on a crisp night—along with damn near every kid on the block—to recreate every winter wonderland scene from the library of movies, tv shows, and cartoons that enchanted us every Christmas. I had a laundry list to get through before the two or so inches of snow melted: Catching a snowflake on my tongue, snow angels, snowball fights, a short, makeshift sleigh-ride down an already-slushy hill. By the next morning, each house had an exceptionally dirty snowman (there really was not nearly enough to build the frosty-white guardians of our dreams) keeping watch over the quickly melting blanket of snow that had so mystified us the night before.

—

I didn’t think about this again until I returned from my undergraduate studies in New England (where snow very quickly lost its charm) to teach high school students in the rural Mississippi Delta. The winters had gotten both progressively warmer, and the weather more erratic. On several days my classes were disrupted by torrential rains and flooding—exacerbated by the expansive monocropping of the Mississippi floodplain, which a century prior had turned swamps and bayous into farmland. Empty desks made it strikingly obvious, from my position at the front of the class, behind the podium, exactly which student’s bus routes—and in some tragic cases, entire houses—were washed away by the flooding: the children of Black farmers and laborers made vulnerable by the confluence of climate change and the entrenched racism of Southern infrastructural planning and design.

When the weather did turn cold, it turned angry: an ice storm and frozen roads in January forced school closures for five bitterly cold days. I lounged around sequestered at home, comfy and somewhat relieved by an unexpectedly extended winter break—but an unsettling thought slipped between sips of hot cider and cocoa—I thought of these same students, many of whom relied on school for a hot meal and a stable environment. The iced-over roads and downed tree limbs provided no respite: They could not even take refuge in the simple pleasures of a Home Alone cinematic snowfall, the way I did all those years ago in suburban southern Mississippi.

—

I recognize that the precarity that my students experienced at the hands of an unstable and wildly oscillating climate is representative of catastrophes accumulating across the globe: Rising seas displacing villages in their thousands; wildfires blocking out the sun; extreme heat and unprecedented storms taxing the power grid to the brink of failure; geopolitical tensions boiling over as ecological collapse is internalized as a pressing military—but not social or economic—concern. But these experiences hammered home for me a less lethal, but no less devastating reality: as these crises accelerate, a relationship with the natural world marked by childlike wonder melts away like those rarified Mississippi snowflakes, replaced by the icy sting of pain, suffering, and displacement—”Nature” becomes a foreboding term. How can we expect a rising generation to grow into stewards of a shared world, when that world constantly presents itself as a spiteful presence, exacting revenge for sins distributed across time and space, punishing those least responsible for the willful negligence of profiteers?

Another painful memory, only a few weeks into my time as a teacher, serves as a haunting reminder of the cruel disparities wrought by our fearful negligence of nature, above and beyond the climate crisis. On a beautiful, sunny afternoon, the principal announced over the intercom that all teachers must immediately draw their blinds, and that no students should be released from class for the next hour. A rare solar eclipse—by all accounts, a once-in-a-lifetime cosmic experience—was passing over our small city; the administration, unlike other districts able to secure sets eclipse safety glasses, directed us instead to protect students’ vision by restricting their movement. I felt so helpless, reluctantly standing guard over my classroom—and angry at the school and at my own lack of foresight.

As I futzed with my projector to open up a livestream—a pitiful replacement—the intercom cracked back to life. One by one, a handful of students were called to the office for early release; their parents had taken off work early to shepherd them, eclipse goggles in hand, to marvel at the natural world. I watched them leave, giddy with excitement; all of them white, middle class students of the majority-minority public school. Just five years earlier, I would have without a doubt tread the same re-segregated route down the hallway, greeted by enthusiastic parents with flexible schedules and disposable incomes, a privileged recipient of yet another “enrichment” activity. As the totality passed, I watched my remaining students glance wistfully towards the cracks in the blinds, a passing shadow and a pixelated projection the only trace of the event.

—

I returned home that day deeply unsettled and dispirited, until my roommate, Phil—who taught at the elementary school down the road—waltzed in beaming, recounting a quite different experience. One of his students’ parents worked at an auto-body shop as a mechanic, and had brought in a huge, polarized, UV-tinted truck windshield, which functionally operated as a massive eclipse looking-glass. The entire class took a brief field trip to the playground, where they crowded around the windshield; Phil’s eyes sparkled as he recounted kids pointing and peering out at the sun, his experience of the students’ wonder and excitement eclipsing the event itself. Amidst the catastrophic failures of our institutions, this second-hand story fosters an abiding faith in the resourcefulness, thoughtfulness, and initiative that our communities can muster—and reinvigorates our collective duty to rekindle imaginations at scales small and large.

-

Hey ya’ll! I’m Jonas, and I’m pretty new to the idea of climate writing—but I’ve been a long-time lover of sci-fi speculation, dystopian critiques, and utopian dreams. I’m a 3rd year anthropology PhD student at Hopkins and the current coordinator here at the EDC. I’m really interested in learning how to tell compelling stories as an ethnographer—and how to draw out and capture climate imaginaries that are implicit, repressed in the narratives of my interlocutors (mostly, rural conservative Americans, who even blinded by denialism are experiencing changes that are impossible to explain). I’ve really been loving clicking thru the Imaginarium’s “Library” (a tab on this group page)… the cover drawings alone are absolutely stunning… https://www.are.na/climate-imaginarium/public-library-for-climate-futures/

are.na

Public Library for Climate Futures — Are.na

A public library and communal repository for climate fiction stories of all mediums, genres, and modalities. Curated by the Climate Imaginarium.

-

I think there’s an interesting aesthetic sensibility to the “ruin” and “decay” that’s also worth exploring; I’m thinking here of all of the things that we design to “look” ruined, from the jump; a sort of nod to a baroque artistic sensibility that reifies a “time before the fall” with its attendant conservative appeal. As a southerner I think about this in relation to “Lost Cause” imagery and monuments that litter the south, and the genre of the “southern Gothic”—which subverts this mythic vision of the past, instead drawing attention to the festering moral depravity that persists in the present; the images of ruined plantations and landscapes overtaken by kudzu metaphorically summoning the rotten bones of society shaped by slaveholding. (Faulker’s A Rose For Emily might be a particularly compelling reference re: southern gothic lit/ the motif of decay).

A the same time, interesting to think about how the “weathered” look signals, very much speaking to our own bourgeois sensibilities, something like authenticity. We want to go to a cafe that feels “lived in”—rather than the sanitized corporate spaces of a Starbucks or a Waffle House.

As an aside, @N_Kulick —Don’t miss our matinee next week! One of the films we’re gonna watch together deals explicitly with themes of decay. Would love to chat with you there! https://community.ecodesigncollective.org/event/tide-pool-social-eco-film-matinee-online/

community.ecodesigncollective.org

Tide Pool Social: Eco-Film Matinee [ONLINE]

Join the EDC this December 20th from 1:00pm to 2:00pm ET for a virtual watch party of two short films featured on the DC Environmental Film Festival’s web repository. We will stream Wrought (2023; 22m) and The Botanist (2017; 20m) … Continue reading