Walking the Highway to Nowhere

A guided tour documents past harms, engages present struggles, and imagines radical possibilities in West Baltimore.

On September 21st, 2023, Ecological Design Collective curator Cristina Murphy and community guides led a walking tour of Baltimore’s infamous “Highway to Nowhere” (H2NOW)—the 1.4 mile ditch that displaced nearly 1,500 residents and separates neighborhoods in West Baltimore. Baltimore City Planner Martin French and community activist Eric Stephenson provided commentary throughout the walk, discussing the bungled infrastructure project and its impact on Baltimore’s historic Black neighborhoods. This walking tour was designed to give attendees an embodied understanding of the devastation that the H2NOW inflicts on public space—with an eye towards the possibilities and radical potentials that lie just over the horizon.

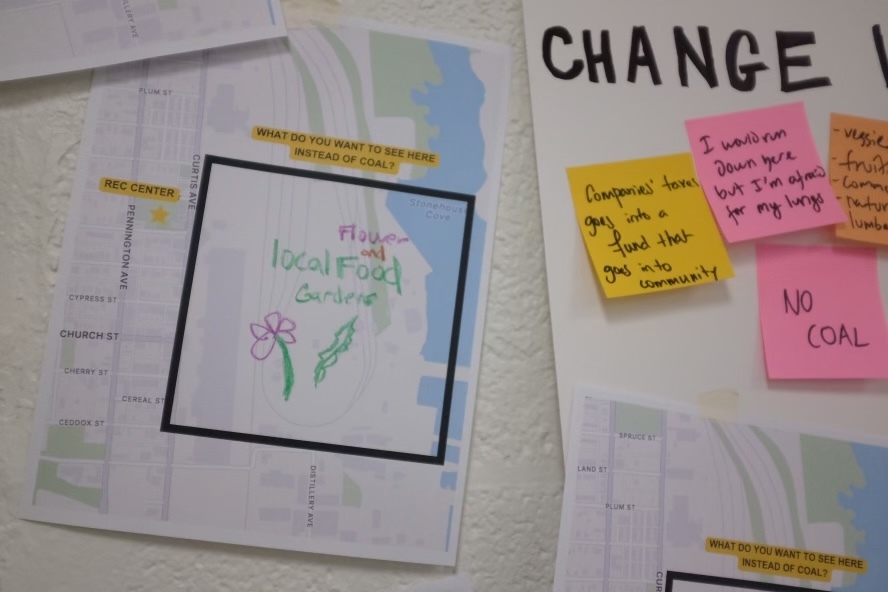

Facilitated by Morgan State University Professor of Architecture Cristina Murphy, this event continues EDC programming on the H2NOW. In January 2023, Cristina’s students presented proposals to transform H2NOW’s six concrete lanes into sustainable community resources—schools, greenhouses, playgrounds (read Cristina’s blog post here). Along this tour, Cristina’s architecture graduate students— Roberson Bateau, Evan Cage, Darren Marshalleck, Tiffany Oduro, and Shamar Roberts presented proposals to refigure the H2NOW into a space for community activism and protest. Check out each student’s presentation of work here— they would love your feedback as they continue to design for social change!

Along our route, the tour had the good fortune to meet resident and community activist Curtis Eaddy, who told us more about the history of the Sarah Ann Street homes, his family’s fight for housing justice, and the continued resilience of communities on the outskirts of the Highway. Learn more about his work at “A Place Called Poppleton,” an ongoing collaboration between the Poppleton Now Community Association, the University of Maryland–Baltimore County, and other community stakeholders.

You can’t see it from the outside, but from here, you really can get a sense of the scale and the scope. I mean, when you stand here, come out here, really come out here… beautiful sunsets to the West… Beautiful view of the city… I mean, just imagine between each bridge was an entire city block. Just the scale, the depth. The width. The length. This is one block. So between Franklin and Mulberry, you know, there would have been a stop sign there, a stop sign there… it’s a whole city block!

—Eric Stephenson, [29:33]

What you’re going to notice is how the highway is an incredible divider between this part of West Baltimore and that part of West Baltimore. Believe it or not, that entire Highway to Nowhere is public property: It belongs to the city of Baltimore. It’s public right-of-way. You may have noticed as we walked up Martin Luther King Boulevard on your left. There was a large area of chain link fencing with plastic and a locked gate— that is public property. But the city doesn’t want homeless people to camp on it, so they’ve got it fenced and blocked.

—Martin French, [18:12]

Look at all that green space and think about how would you get there if you wanted to— because you can’t without risking your life. Your life! And then the other thing… Fremont Avenue is right here and is like a diagonal artery from from West Baltimore down to the harbor; that is interrupted. We saw all the bridges that reconnected a lot of the grid streets— but Freemont Avenue was never reconnected by a bridge section. But people are like water; they find the shortest path. And so there’s a cow trail or a footpath where people on a daily basis do that: [pointing at pedestrians precariously crossing the highway by foot] Every. Single. Day.

—Eric Stephenson, [53:08]

Today, some of my students are here and they are looking at it [the Highway to Nowhere from the] point of view of: What can we do to make things a little bit more respectful? What if this becomes a place keeper, it’s an installation and it’s a place for protest? So we are designing an installation on paper. Hopefully one day we will have the budget to design it, to build it as well, where people can express themselves and protest.

Assuming that the highway —this is the synopsis of the course— that the Highway to Nowhere becomes obsolete and it’s taken over by people and declared as the largest public space in North America. We ask: Can we design for protest? What is public space? How is democracy spatially recognized? How should a democratic space look like?

—Cristina Murphy, [04:09]

I think one thing that everybody needs to keep in mind is when you tear down houses, you tear down a neighborhood, you’re not just tearing down the physical buildings and you’re not just moving the people who live there to some other place, whether they like it or not. You’re also wiping out memories. You’re wiping out something that’s a part of a family.

—Martin French, [1:01:00]

Read the complete transcript here:

Photos by Cristina Murphy, video by Jonas Johnson

ABOUT THE GUIDES:

MARTIN FRENCH has worked for the Baltimore City Planning Department since 2004. After five years in the Research & Strategic Planning Division, where he was a contributor to LIVE EARN PLAY LEARN, the City’s Comprehensive Master Plan, he began working in the Land Use & Urban Design Division as the Department’s representative at zoning hearings. Apart from this principle responsibility, Martin is part of the LUUD team advising developers and citizens about possible development or redevelopment and how zoning may shape outcomes of those ideas.

ERIC STEPHENSON is Vice-Chair of the Baltimore City Planning Commission and a resident of West Baltimore. He’s a member of several community organizations including the No Boundaries Coalition Board, an advocacy organization unifying Central West Baltimore, and the Harlem Park Neighborhood Council where he serves on the housing committee. Eric is also a 2019 alumnus of the Department of Planning’s Planning Academy. Eric works as a Project Manager for Southway Builders, a Baltimore-based general contractor specializing in affordable housing, mixed-use commercial, and school construction.

FURTHER READING:

Paull, E. Evans. 2023. “The Anatomy of a Bad Decision.” Stop the Road (blog). June 22, 2023. https://stop-the-road.com/the-book/2023/06/22/the-anatomy-of-a-bad-decision/.

Equity in Planning Committee. 2017. “Racism in the Structure: An Overview of Baltimore, Maryland.” Baltimore, MD: Equity in Planning Committee. https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/l683c3pni7tkyw14jy4fz/Equity-in-Planning-Committee_2017_Racism-in-the-Structure.pdf?rlkey=61b4bv13332e5kximi1qrbly1&dl=0

Eric Stephenson, dir. 2023. Highway to Nowhere. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=01AunlcqDFc.

Lucas, Amanda K. Phillips de. 2020. “Producing the ‘Highway to Nowhere’: Social Understandings of Space in Baltimore, 1944-1974.” Engaging Science, Technology, and Society 6 (October): 351–69. https://doi.org/10.17351/ests2020.327.

Responses